“To keep global warming below 1.5°C this century, the world needs to urgently put additional policies and action in place to almost halve annual [global] greenhouse gas emissions in the next eight years.”

UN Emissions gap report 2021

We – the human race, all 8 billion of us in 2023 – currently pump 53 gigatonnes (that’s 53,000,000,000 metric tonnes) of greenhouse gas into the atmosphere each year. Every time we fire up the central heating, or the car, or the TV, or tuck into a plate of food, or build an extension on our house, or buy new stuff, we are producing an amount of greenhouse gas that contributes to this total.

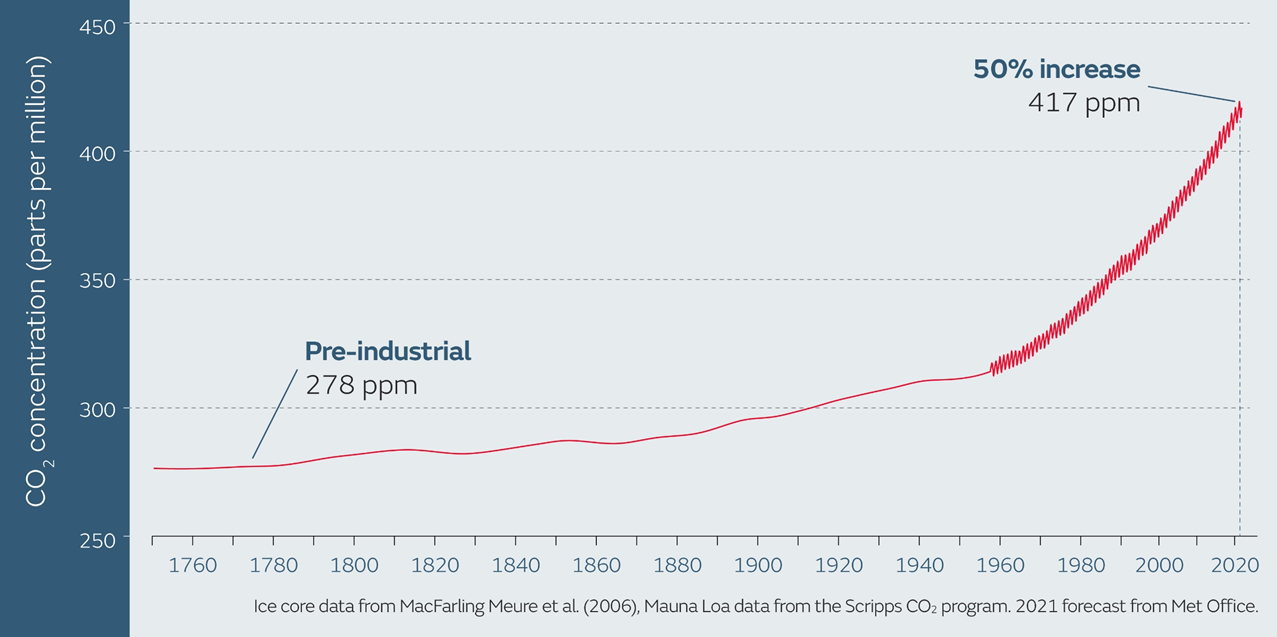

As we know, these greenhouse gases have built up in the atmosphere since the start of the Industrial Revolution, and have heated our world by over 1.2 celsius already, with serious consequences for our weather, our daily lives, food security, and our wildlife.

Many agreements – such as Paris Climate Agreement in 2015, signed by every country in the world – and many others like it that have been signed over the past decades. There is clear agreement among nations that we must limit global average temperature rises to 1.5 degrees celsius above the average levels last seen in 1990.

Yet in spite of all these agreements, and all the pledges and stirring words of a multitude of world leaders, greenhouse gas emissions have continued to soar. Here’s the graph from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the UK’s Met Office, showing the meteoric rise of greenhouse gas emissions since the start of the industrial revolution in 1769.

So, the greenhouse gas that we put into the air each year has led us to the point where we need to reduce concentrations very rapidly.

But all these huge, global level figures tend not to make much sense to most of us. We need to break them down to an individual level to see what they might mean for us.

How we get to three tonnes

If accept that we are human, and that our daily activities produce greenhouse gas, we can also then divide the total amount of gas we produce annually by the number of people currently on the planet. In 2022 this is 8 billion men, women and children, producing 53 gigatonnes of greenhouse gas. From this we get a global average of approximately 7 tonnes of greenhouse gas per person; enough to produce further huge climatic shifts that we would all really struggle to deal with if we continue.

The range of target emissions produced by the InterGovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 2018 put the target global emissions at 25 gigatonnes per year by 2030. This is an average of 4 tonnes per person each year. However, the world population will likely have increased to 9 billion people in 2030, so we need to take account of that too.

Therefore, we arrive with: 25 gigatonnes divided by 9 billion people: an average of three tonnes of greenhouse gas per year for every person on the planet by 2030 if we want to have a realistic chance of limiting the worst effects of climate change.

Of course, from there, we need to push on even further to drop global emissions to around 1 tonne per person – and develop a lot of different strategies to remove the existing surplus carbon from our atmosphere. But meeting the target of 3 tonnes by 2030 crucially buys us more time to achieve the longer term goal of 1 tonne per person, and develop better large scale methods for extracting and storing the greenhouse gas that is causing the problems.

Silver Bullets and Blame Games

The climate debate has been filled with ‘silver bullet’ solutions over the past twenty years or so. Stop burning coal. Stop eating meat. Stop flying. Carbon capture and storage. Equally, the blame game has been in full effect: It’s the Chinese power stations. It’s the huge birth rate in the developing world. You can insert your favourite silver bullets and blames here.

The truth is that we have all – collectively – delayed doing anything for so long now that we all have to do most or all of these things and more. But how do we know if we are actually getting near to where we need to be? Are we making a virtue out of the things we don’t do anyway in the name of the climate, or are we giving up the things that make life worth living when we don’t have to? This can be a confusing quagmire, and being humans, we tend to fill this sort of space with irrational thoughts, justifications, backed up with headlines from the media. That is why we need….

Three tonnes as a rule of thumb – and an antidote

Call it a target, a goal, or just a decent measuring stick so we know we are heading the right way, we need this three tonne ‘rule of thumb’. Why? It helps us to plan, to prioritise, to focus. It can help us to choose, to preserve the things that really matter and jettison the high carbon activities we can actually do without. It can help us to feel better – good even – about our choices, instead of feeling secretly (or openly) guilty. We know when we are going in the right direction.

Most importantly from my perspective, it allows an element of individual choice. There are no ‘rules’; the only constraint is the overall footprint target. There are many different ways this can be done.

But is it even possible?

At a first glance, achieving a three tonne footprint looks extremely difficult for most of us. The average carbon footprint in the UK is around 12 tonnes per person per year in 2023, so its a 75% reduction in 7 short years from the time of writing this post in 2023. There is no doubt this is a big ask.

It is worth bearing in mind though that although reductions in our average footprint in the UK are large, half the world’s 8 billion population is already producing less than three tonnes a year. Emissions are very closely linked to wealth: the wealthiest 10% of the global population produce half of all global annual emissions each year (1), often with an annual footprint of 18 tonnes or more. If we live in Western Europe or North America, that is likely to be us. The wealthiest 1% of the world’s population will have a footprint of 50 tonnes a year, or more.

That is not to say that it is the wealth that is wrong. Rather, we need to break the link between wealth and the consumption that produces very high emissions. And as wealthy individuals – which most of us living in Western Europe or North America undoubtedly are in global terms – we have a lot of personal and financial resources that we can dedicate to this.

We are likely to hit 1.5 degrees celsius of warming in around 2030 at current emission levels, so there is a large degree of urgency. And what we do now will define whether temperatures continue to climb in the coming decades, or level off and start to fall.

So there is a long way to go, and very little time. But it is achievable, if we put our individual and collective will to it.